(Para o texto em português clique aqui)

The Rediscovery of the Arcade Cabinet

These past days, I saw the beautiful new arcade machines by the folks at Game e Arte on Instagram—a project by Jaderson and Tainá in São Paulo—entirely crafted from wood. Talking to Jaderson, one of the creators, inspired me to write a few words here.

But let's start at the beginning—or my beginning—because that's what first sparked something in my mind. Since entering art school, I’ve tried to incorporate video games into my creative work. Initially, in a more basic way, I explored the aesthetics of old games—pixel art, low poly—to create visuals in painting, drawing, sculpture, or wherever I could.

In 2012, I created a “video art” installation using RETROBLUE, the second arcade machine I built. It featured the pioneering game Pong, but as the player tried to play, programmed alterations in the rules and timing, accompanied by sound, disrupted the gameplay. (The paper list shows the lines of code used to modify the game.).

The goal was to play with game rules, drawing an analogy to life under capitalism, where rules are changed at the whim of a small bourgeois minority. But the important thing here is the arcade machine and how people interacted with it. We'll revisit this later.

Fast forward to 2014. When I decided to make games with students at the public school where I taught art, I felt compelled to research others doing similar work. That’s when I found Pedro Paiva, also making games with students, often under even more challenging conditions. Like me, Pedro had (and still has) a blog where he reflected on his experiences. He was the first to realize the importance of the arcade as a strategy or device to bring games to people while challenging the restrictive logic of the industry spaces.

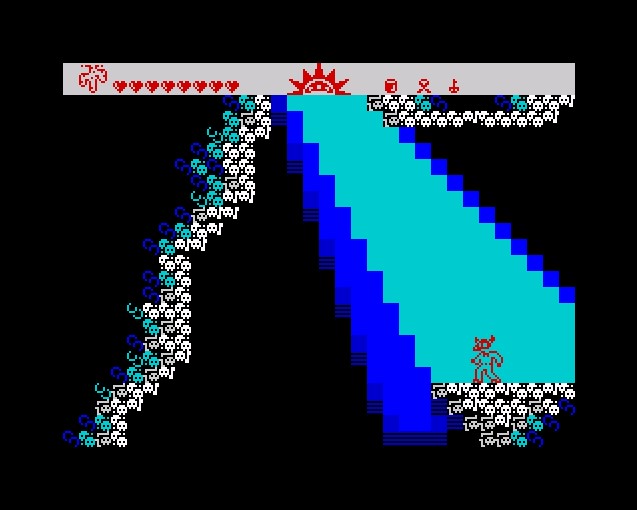

Image: "Pirata de Prata," the first of several arcade machines created by Pedro Paiva. Image from his blog post:

https://menosplaystation.blogspot.com/2019/06/antigamer-enquanto-antifascista.html

The Arcade as a Break from Routine

Pedro Paiva sees the arcade not just as mere "packaging" for a game. Being a medium to bring games to public spaces, the arcade cabinet or furniture becomes part of the game itself. Like a "zine," the aesthetic choices regarding the arcade's form convey something beyond the content being written—or played, in this case. There's much more to this concept than I can summarize here, but I recommend reading Pedro’s texts on the "Fliperamosfera" (https://menosplaystation.blogspot.com/2019/11/pirateando-oakland-videogame-rueiro.html) and "Zinerama" (https://menosplaystation.blogspot.com/2020/07/zinerama.html) on his blog.

Building on Pedro’s reflections, our dialogue, and my own experiences of bringing my games to people through arcades, I believe that the arcade furniture itself is an artistic device. This isn't just a flattering description to “elevate” our work, as if calling it “art” magically legitimizes it. Rather, it's because arcade machines, even before someone plays the game, transport people to a differentiated space and time outside their daily routine.

When people see an arcade machine, they’re transported elsewhere—to a non-routine space. For older generations, nostalgia plays a role, but it doesn’t stop there. What delights me most is seeing how children of all ages, with no prior relationship to the object, are equally captivated. It’s not nostalgia but a kind of “magic” that the unusual object creates.

The arcade invites collective play. Children gather around, take turns at the controls, watch their friends play, and share opinions. As Pedro Paiva notes, this effect is even stronger when each arcade, or series of arcades, has its own personality. The more unique its materials and design—whether it has a name or uses unconventional materials—the better.

Image: From left to right, "Pirata de Prata," "Cavalo de Santo," and "Capeta Compiuter." Image courtesy of Pedro Paiva.

For instance, each of Pedro Paiva’s arcade machines is unique, with its personality and singularity. The recent arcades from Game e Arte are distinctive too—crafted from rustic wood rather than laminated MDF, but still unmistakably arcades. I also strive for individuality in mine, with the Anakrôniko Arcade, made of PVC pipes and fabric, being my most "alternative" model. Each has its aesthetic impact, adding to the game and helping create this break from “normal” time, unlike mainstream video gaming, typically played at home as a continuation of daily routine.

It’s well-known that placing an object in an “art gallery” changes how it’s perceived. A urinal in a bathroom or a banana at a market is what it is because it’s in its “proper place.” In a gallery, these objects become something else. Whether people debate their validity as art isn’t the point. What matters is that objects “displaced” from their “natural” context disrupt the space and time of the everyday. What’s intriguing about the arcade, as reappropriated by independent gaming, is that no matter where it’s placed, it creates a disruption—not because of the gallery environment, but because the anachronistic object itself causes this discontinuity.

Image: The infamous banana in a gallery that sparked online controversy.

This effect extends further when our games contain “uncommon” cultural elements: local settings, folklore, stories, recontextualized pop culture characters, or references to cinema and literature. These elements tie games to real-life experiences, far removed from industry clichés. While there’s much more to say about this, the focus here is the arcade and its effects.

In summary, our arcades are part of the work, in tandem with the games. An arcade machine is an aesthetic object that displaces people and serves as an uncommon interface for interacting with the game. The large controls require broader physical movements, which add to the disruption of everyday space for the player. Above all, these objects are anachronistic and unexpected, inviting players to break away from norms—even for those without nostalgic ties—because they are more than mere “objects”; they are interfaces, devices for our games.

I won’t repeat myself further, so I’ll end by sharing some related links:

Pedro Paiva:

https://menosplaystation.blogspot.com/

https://bsky.app/profile/pedromenos.bsky.social

Game e Arte:

https://www.gamearte.art.br/blog

https://www.instagram.com/talktogamearte/