(Para ler o texto em português clique aqui)

Marlow ZX “Post Mortem” or Reports and Reflections on the Creation Process

After working on Bruxólico, a big game project for the ZX Spectrum, which also involved all the work of creating a narrative, book, and countless illustrations, I wanted a smaller project. I thought that Marlow in Apocalyptic Acid World would be a quick and straightforward project, something to complete in two months of "hyperfocus." I couldn’t have been more wrong.

A Super Mario clone is not as simple as you may think

By today's standards, Super Mario (1985) seems like a simple game. After all, you just jump on platforms and enemies to defeat them, right? But the truth is that this type of game requires a series of different interactions between the player and various objects, such as breakable blocks, enemies, power-ups, platforms, etc., etc., etc. Making all of this fit into a ZX Spectrum game, or even a small NES cartridge like Super Mario (40Kb), is a huge puzzle that can only be solved with careful planning about what to include, what to leave out, and what should be reused multiple times in the game. Making the game for PC, as I did in 2016, is a bit simpler because you have access to many more resources for graphics, sounds, screens. But making it for systems with limited memory is a whole different story.

“Test pixel art for sprites aiming to minimize animations and thus optimize memory usage”.

A lesson in game and level design

Both in its many successes and innovations for its time, as well as its "mistakes," which Shigeru Miyamoto tried to fix in subsequent versions of Super Mario on the NES and SNES, the 1985 game is widely recognized as a lesson in game design. So, my first task was think about this, trying to understanding what I should modify for my own purposes and limitations.

The so-called "simple" mechanics of a game like Marlow are not exactly "that simple," and as you start programming, you begin to notice exceptions within exceptions that are needed in the code, making everything much more complex. The player breaks blocks with their head, but only when they are "rising" from the jump, not when they are falling. There are different types of blocks that give different items, even when the block uses the same graphic (which, to avoid wasting memory, cannot be repeated). There's also the interaction with enemies: some can be defeated by jumping on their heads, others only with the Molotov, and some are invincible. To complicate matters, Marlow has 3 different forms, and each form brings its own exceptions in interactions due to altered speed and the Molotov. And then there are the underwater levels, where jumping and the speed of everything are modified. Not to mention the moving platforms in different directions. When you combine all of this, the modest ZX Spectrum struggles, partly because of its limited processing power and partly due to my limitations as a programmer and the MPAGD engine, although I tried to optimize all these exceptions, which certainly added a lot of code to the program.

“Planning to fit the screen sequence into the limited MPAGD map, which provides space for 8x16 screens for the full map”.

A common practice in game and level design is the gradual layering of challenges and obstacles. You take simple obstacles and challenges, introducing them one at a time, from the easiest to the hardest, and then start combining them in different ways. In Marlow, with the current engine I use (MPAGD Gen2), I was able to get about 40 unique game screens, a limited amount for a dynamic game. Therefore, as usual, I had to "recycle" screens, repeating them with small changes, like a new enemy or a block with a different item. For this reason, I chose to make the final screens of the level (the screen with the antenna mast and the one before it) as standard screens, but also aware that this creates a certain effect: when the player recognizes these screens, they know they are close to the end of the level, which changes their sense of urgency. I believe, depending on the person and their previous moment in the game, this can either bring a sense of relief or increase their tension.

“Hand made level planning for the first stage of episode 2 with screen repetitions and modifications”

Super Mario is a game designed with screen scrolling in mind. Marlow, on the other hand, is designed for its main stages to use the "flip screen" format, where there is no screen scrolling (camera movement) and you move from one screen to another as if flipping the pages of a book. This changes some considerations when planning the challenges: the player enters a new screen and must look and "read" everything in front of him, understanding how the elements relate to each other, and then decide on a course of action. Unlike screen scrolling, which brings new elements into the player's "horizon," requiring more dynamic adaptation, here the player almost separates these actions: identifying the elements and then acting. However, when they reach the end of the screen and "turn the page," a new screen presents itself with many new elements at once, requiring quick thinking or a pause to reflect. The result, I believe, is this almost distinct separation between evaluation and action, something that happens more simultaneously in a scrolling game but in a more fragmented way, since the player doesn’t have that first moment of seeing the entire screen at once. This is something that reminds me of the "page-turning" effect of a book or comic, and it brought to mind the strategies of surprise, breaking, and continuity present in those other media.

The memory limitations and the need to "recycle" graphics and code also made me think about the game's "bosses." Super Mario also recycles a lot of screens and content to fit into 40 KB, to the point that the 8 stage bosses are always the same: Bowser on a bridge in the castle, or false Bowsers, with the eighth being the final and true villain, always in his castle. Thus, I felt comfortable repeating elements as well: instead of castles, Marlow has towers, and the stage bosses are different (though fundamentally similar, using the eye sprite), with the towers preceding them being the same. Just like in Super Mario, the boss battles are short (though slightly and gradually longer), serving more as a stage-ending marker than an long challenge. It’s no coincidence that I placed the higher difficulty in the elevator section that ascends the tower, keeping the bosses relatively easy to defeat.

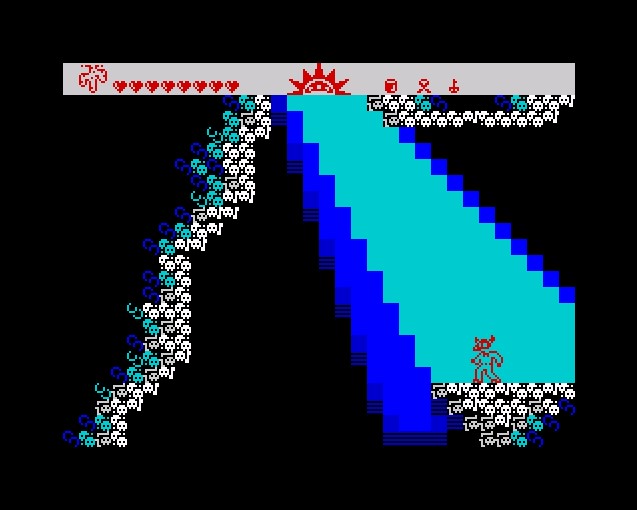

“Screenshot of the first boss in Marlow”

To conclude this part, I wanted to talk about the stages. I also created a structure similar to the one in the first Super Mario, where each of the 8 worlds essentially repeats the same sequence: an "overworld" stage, a second underground or underwater stage, a third stage on “ hills” or with more bottomless pits, and the fourth stage inside a castle with a boss at the end. In Marlow, I also chose to have the overworld stage first, followed by an underground or underwater stage, with the third stage simulating a "forced horizontal scroll" (to add variety and have a different kind of stage, using some extra code but saving many screens), and the tower stage replacing the castle stages.

Another important detail: in the early Mario games, the stages don’t have names, just numbers: 1-1, 1-2, 1-3, etc. The game displays the “World” number followed by the stage number. This changes in Super Mario World on the SNES, where areas have their own titles, giving them more personality. However, my inspiration for naming the stages in Marlow came from another source: Sonic the Hedgehog on the Mega Drive. I believe Sonic evolved this idea by giving stages names that contribute to create the game’s universe. They function like the title of a painting in a gallery: the title of an artwork can be an important element, even changing the meaning of the image. With that in mind, I chose the names for Marlow's stages, even though it eats up precious memory, as all text is “expensive” in terms of memory in the game’s programming within MPAGD.

Narrative elements and cultural references

I wanted to start this part by talking about something I value and take great care with, which is always doing at least a fast research on the cultural references I use to create my game or any other work of art. I do this for two reasons: one, because I consider it the bare minimum, the “homework” of any conscious creator, and also because I want to be careful and respectful towards objects or cultures from groups I may not belong to. Recently, someone commented on social media that they found my use of music in Marlow "brilliant," which I’ve already detailed here on the blog. I thought about it for a while because, honestly, I don’t consider myself a genius, and this isn’t false modesty. As I said, what I did I see as the "homework"— the minimum research that should be done. It doesn't have to be in-depth research, but the basics, like doing a quick internet search, reading something on Wikipedia, and taking notes of the the main information. For Marlow's music, I did all of this in one morning. When someone called me a genius for doing the basics, I wondered: if people think that’s genius, am I the one-eyed man in the land of the blind? I really hope not; it's more that many people simply lack the practice.

Well, Marlow, the main character, is an anarchist in an apocalyptic, dystopian future. It's worth mentioning that I’m not personally an anarchist, nor a great reader of Bakunin or other thinkers in the field. At most, I have an personal nature that was influenced by the punk culture of the 80s, which "exuded" fragments of anarchist thought, as well as a typical 90s grunge nihilism — both sources I drew directly or indirectly as a teen. But I tried to represent Marlow's anarchism with the respect that any culture or ideology deserves. If Alan Moore can use these references, as he did in creating V for Vendetta, why couldn't I do something similar?

But let's go back to Super Mario. Reflecting on it, I came to a conclusion that might be obvious but had never crossed my mind: the world Miyamoto created is clearly inspired by Alice in Wonderland, more the Disney version than Lewis Carroll’s, it’s important to note. Whether this was a direct or indirect inspiration, the fact is that Super Mario still carries a kind of surrealism that’s almost psychedelic, although significantly toned down for a children’s audience crafted by the cultural industry. With this in mind, it’s clear that Marlow also needed to have this surrealism character even more explicitly. It’s no coincidence that I ambiguously included "Acid" in the game’s subtitle.

“On the left, Disney's Alice (1951) in a world with giant mushrooms and strange creatures, on the right, a scene from the Super Mario movie (2023)”

An idea I’ve had since I started making games in 2013 is to take classic game genres and styles (at least classic to me), like Super Mario, Castlevania, Mega Man, and others, replicate their gameplay mechanics, but insert my own original universe, with characters and narrative situations that interest me and are culturally more diverse. Now, I love these games — they left a mark on me, and I can still play them (when I have the time and patience). But now I’m 43 years old and I can recognize that they don’t have adult content — they are at most products aimed for teens, although they sometimes do have potential for more.

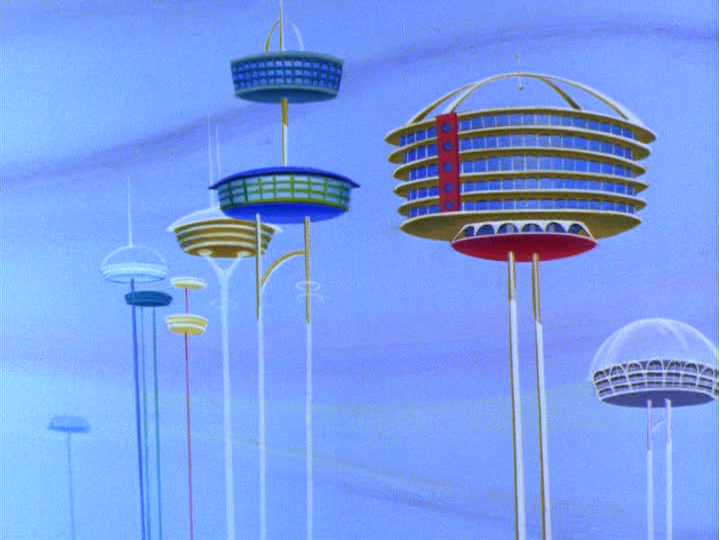

And this is one of Marlow's principles: to play like a Super Mario game, but changes for a more mature content. Instead of a somewhat “harmless” character, in the Disney mold, like Nintendo’s plumber, we have Marlow, an anarchist who throws molotov cocktails and attacks the bourgeoisie. Instead of the cute "mushroom world," we have an apocalyptic world, somewhat more surreal and psychedelic like in Mario, but with different content. The castles, a representation of the monarchy that lost power to the bourgeoisie in the past, are replaced by "panopticon towers," from which the “landlords” (not “bosses” anymore) surveil that world or society.

“Towers where the characters from "The Jetsons" live, a utopian and futuristic vision of the "American dream" that has always left me wondering: but what’s in the world below the towers?”.

I also need to talk a bit about the music and how it composes the game world. We know that the 1985 Nintendo game has iconic and memorable tracks. The game starts its "overworld" levels with an upbeat song, in major scales, that creates a desire in the player to advance. The underground levels feature music that builds tension and expectation, signaling to the player that they should act with caution. The water level theme is a waltz, with its 3/4 musical meter, slower and accompanying the player’s movement in the water. Finally, the castle music is the most tense, alerting the player that they are within the enemy’s base. I used this same structure, also taking into account the origins of each piece of music.

As I’ve already published here on the blog, the music in Marlow isn’t my original creation. They are all melodies from anarchist or antifascist resistance songs from the 19th and 20th centuries. It made perfect sense to choose these songs, as they contribute to Marlow's relationship with the anarchist tradition. All songs are in the public domain and often borrowed melodies from other popular, even older, songs. I researched and listened to these and others, and then made a selection considering what I mentioned about the music of Super Mario in the previous paragraph. The only song that deviates from this is "Bella Ciao," which I use in the forced horizontal scrolling phases. Here, the connection came from Super Mario 3 on NES, which features similar levels with an accelerated song that creates a sense of urgency. Finally, I wrote and programmed the version for the ZX Spectrum’s sound chip (3 channels of square waves and white noise) for each of the chosen songs, adjusting their tempo and rhythm to my needs while keeping the melody recognizable. The details of each track are in the synthesis of the research I conducted and published on the blog and in the game’s “read-me.txt” file (click here to access the post).

Anachronistic Videogame

As a final chapter of this post-mortem of the game, I want to recall the dialogue this work has with the "Manifesto of Anachronistic Art," by the Gang do Lixo group, of which I was a part, and which was mainly written by my friend Luiz Souza. He succinctly captures things that embody the spirit of our time, which are becoming increasingly urgent, especially in light of the dehumanizing changes of capitalism, such as these AI technologies. I recommend reading the manifesto (click here to read the manifesto) for anyone interested in the following paragraphs (click here to read the manifesto).

As Luiz Souza summarized, never before in history have we had such an accumulation of reproducible culture that is, in a way, accessible as it has been in the age of the internet. We might have had books and paintings, but cinema, recorded music, cheap prints like newspapers and comic books have left us with a varied and diverse accumulation, partly due to their reproducibility and subsequent digitization and availability online. Yes, a lot of "garbage" from the cultural industry has shaped my generation, especially in the third world, where we had limited access to other cultural goods that could balance out the packaged content shown on TV. However, we became specialists in cultural trash, sifting through interesting fragments, quotes from other classic or contemporary art works amidst the morning cartoons, video games, radio music, etc. We are cultural trash miners. It's worth noting that, like any mining operation, this process can be somewhat violent and fraught with problems. I will return to the topic of the Manifesto of Anachronistic Art before concluding.

One of the inspirations for Marlow is the work of my friend Pedro Paiva (Click here to access Pedro's Blog). Pedro has been doing a very, very important job in the Brazilian Indie video game scene. Like myself, he weaves together references from pop culture, especially from the peripheries, with references from art history and his political readings, infused with fantastic humor, without getting caught up in trends, truly doing independent work. In addition, he reflects on and shares experiences with arcade machines to get his games to the streets. What Pedro does is, to me, an anachronistic video game in the sense of the aforementioned manifesto. I need to make it clear that when I created the first version of Marlow in 2016, I was also inspired by Pedro's work.

"Telethugs, a game by Pedro Paiva that appropriates elements of pop culture and subverts their use".

Returning to the topic, the Manifesto of Anachronistic Art was completed and published in 2022 not by coincidence: it marked the one hundredth anniversary of the Modernist Manifesto, a document in the history of Brazilian Art that resonates to this day, echoing in movements like Tropicália and Manguebeat, both of which, in their time, updated and connected their ideas to the social realities of Brazil. I say this to clarify: our manifesto of 2022 also carries a political message that emphasizes the importance of local culture, without closing ourselves off or neglecting to "consume" the culture of others. But, as it is well stated there, now it is necessary to anthropophagize not only through geographical space, seeing the other as foreign, but also to anthropophagize through time: others are also ourselves in time.

This already happens, even if unconsciously, and its assertiveness became even clearer starting in 2023 with the "boom" of image automation technologies and other productions. These so-called AIs (sic), which are not conscious intelligences as some think, but automation programs for generating cultural products based on vast databases of human production of images, texts, videos, and other content available on the internet, articulated by algorithms and technologies that reconstruct something from fragments. These technologies "consume" all the culture that the Manifesto of Anachronistic Art refers to, and literally vomit a mash. Much in the spirit of our time, this is an unconscious anachronistic use of people by these tools (did I mean that people use AIs or that AIs use people? I don't even know). The manifesto becomes even more relevant as it calls people to adopt a conscious stance in cultural creation that is anthropophagic in both time and space. We need to consciously utilize this repertoire of human production that has been stolen by large technology monopolies, but as human beings, to continue creating human art in the face of the flood of automated and vomited production that will fall upon us.

I believe that the Marlow game for the ZX Spectrum is my most recent attempt in this regard, as are my previous works and those of Pedro and other artist friends from various fields who follow the same path. I think that against this future of AIs (sic), we must create by reappropriating and using the cultural repertoire that the Manifesto of Anachronistic Art discusses and from which they try to alienate us, inundating us with fifth-hand products. Ultra-processed culture is the new stage of capitalism under AIs (sic), a step beyond the packaged products of the 80s and 90s. I always mention, when creating new games for obsolete machines, programmed obsolescence and how counterproductive it is for aesthetic advancement. However, what this future of AIs (sic) tends to do is not just render cultures obsolete but to render certain social strata (always the lowest, and now finally the proletarian layer of the "middle class") obsolete in capitalism. When you become obsolete, what remains?

I conclude with an appeal in line with the Manifesto of Anachronistic Art: create art, make your creations with the materials and skills you have at your disposal, no matter if they are trash or if you think what you produce is "ugly." Any "ugly" human product is better than AI (sic) mash. Have a third-worldist mindset, akin to those who live off the scraps of capitalism in the suburbs and urban peripheries: create with the raw materials you have available. If I had waited for ideal conditions, I would never have made a single game, nor would I have left my banking job to pursue a degree in the arts, nor would I have produced everything I have during this time and even before. Since childhood, I have drawn with whatever pen and paper I had on hand, even if it was lined paper or advertising flyers, following the example of my father, who I always saw drawing on any paper or during any free time he had. Also, consciously seek to appropriate the cultural accumulation of humanity that is available on the internet, for that is still (still) what we have at our disposal. Don’t wait, and don’t be precious about raw materials, whether material or cultural.

Amaweks, Florianópolis, October 2024